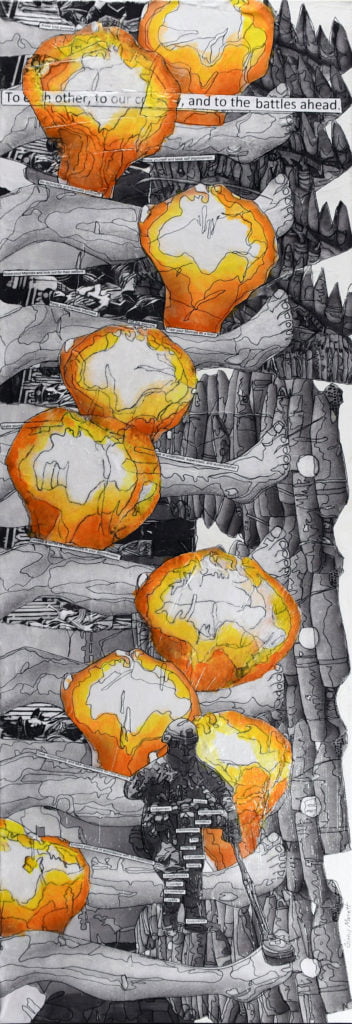

Ginny Merett

12” x 36” • Multimedia Analog Collage

I’m honored to participate in the Bullets and Bandaids exhibit this year. I’m doing so in honor of my dad and uncle’s memory and for their service to our country. I created this piece after reading the story of a Marine who served in Afghanistan as an officer. It wasn’t easy reading this story or making this piece, and I certainly feel like I didn’t do his story true justice, but my intention was to show his dedication to leadership under terrible circumstances. This multimedia collage was made with photocopies, acrylic paint, and photo skins. I repeated shapes and content to represent patterns in war as referred to by the veteran whose story I depicted, and to emphasize the casualties of war. And I referenced the Marine Corps traits and principles of leadership using text.

Inspired by the experiences of Rob Rain

Rain Falling Up

Interview Edited by Compton Bailey

There are four stories I can think of that are indicative of what we did.

The first is when we had an Afghan soldier get wounded. I was at the base, not on the patrol where it occurred. An Afghan soldier stepped on an IED and lost both legs. The Marines that were on the patrol started moving towards him, and the Marine with the metal detector stepped on a second IED that did a low order detonation, which means it didn’t go off all the way; just the blasting cap and a little bit of the homemade explosives. The Marine broke or sprained his ankle, but wasn’t seriously injured, and crawled out of the way. These were what we would call toe-poppers. They’re pressure plates that are useless against vehicles. Purely for targeting dismounted troops.

The navy corpsman on patrol, knowing there were probably multiple IEDs in the alley, but seeing this Afghan soldier that had lost both his legs, ran the rest of the way through the alley and tied the tourniquets on his legs. He was betting he wouldn’t step on one, or was willing to take the risk. He got a silver star for that and a couple of other things he did. Then the marines carried this Afghan back through the alley, knowing there were IEDs there, willing to risk themselves for him. They got him to the compound while taking fire and called in the casualty evac.

The helicopter came and suppressed the enemy fire, but it turned out that in the crossfire, two young boys who had climbed onto a roof were hit in the crossfire. As the helicopter landed, loaded the Afghan, and left the compound the father of the boys brought them over. One of the boys had survived, and so the helicopter was called back. The other boy was dead. This was a few miles away from where I had just arrived with our quick reaction force.

I had to sit and talk with the father whose son died fifteen minutes prior. The whole village after that. Somehow he’d gotten caught in this crossfire. Everyone knew that. That was clear. Obviously the Taliban didn’t intentionally target him and neither did we. Somehow he was killed. They were upset, but I think they were frustrated at the war, not us. They knew that we weren’t going around busting into people’s houses. We were very careful with how we treated the locals. We sat with them. There’s only so much that words can express, but we didn’t make excuses.

I said “this is what happened. I’m so incredibly sorry.” Obviously, we made restitution. It wasn’t clear how he got shot, other than that, clearly, he was in the line of fire between the Taliban and our positions. And then the locals didn’t really blame us. These were people we lived with. We had another patrol base in their village. So these were folks whom I think genuinely trusted us. The situation was traumatic for everyone involved in it. The marines were pretty upset that this had happened. Unfortunately, that sometimes happens in an urban area. There was another time a little girl got hit by some shrapnel, but that was the only time that someone who was very clearly a civilian was killed. I think the boys wanted to see what was going on.

The second major event was the first ambush we executed. We worked with the Afghans Police to set it up. We would do this a lot with other ambushes in which they or the militia members we hired to work for us would dress in their civilian clothes, and we’d go into Taliban controlled areas. We set up checkpoints that the Taliban would think were theirs because of the Afghans there in civilian clothes.We killed the number three high value target, number four for the battalion, though we didn’t know it at the time. When he came in, didn’t want to be captured. He was armed and as soon as he realized there were Marines there, he tried to get away and was killed. We carried his body back to our base. That was maybe the second one we recovered. Later, we realized that he was a high value target. It was a big deal for us, to feel like we’d knocked out one of the leaders. We had killed a sub commander before then in a strike, but we hadn’t gotten someone of that level.

The third event was the next major casualty event for us in November, where I saw the most courageous thing I’ve ever seen. I was in a meeting with village elders when some marines were on a security patrol about 800 meters away. One of the Marines, Richard Chavis, stepped on an IED and became a double amputee kind of right at the knees. We heard the blast and our immediate reaction, when someone is seriously injured, is a red flare because everyone can see it coming. I immediately ended the meeting and went there with our quick reaction force and EOD coming out of our main base that I commanded. And then our little patrol base sent out Marines.

They were probably only a few hundred yards away. They got to the site to get Chavis out of there. The corporal that was bringing the second group got to the field where the first marine and SOP were. Someone gets injured like that, obviously, you immediately try the tourniquets, and then you get out of the area to take cover, but we were not being attacked. When the second group of Marines that got there, Brandon Rumbaugh, who was the corporal in charge of them, stepped on an IED, maybe 20 feet from the first marine. He lost both his legs.

The Marines in the field knew they were in a minefield and that there would be more, so they tied off the tourniquets and froze. Around the time I arrived, I remember throwing my radio to one of the scout snipers and telling him the grid I wanted the helicopter to land on. We’d done all this before, we knew what we were doing, the bird was already on the way. I went down an alley to look at the field and got there at the same time as the head of our EOD detachment, a guy named Staff Sergeant Kindvall.

I remember thinking “how on earth are we going to get these guys out?” Brandon Rumbaugh had already turned that ashen gray that you turn when you’ve lost a lot of blood and are in shock. I thought we were going to have to sweep with a metal detector to get to each marine and then drag them out and up to where we were landing the helicopter. Kimvall recognized that there wasn’t time to do a detailed, deliberate sweep of the area, probing each metallic kit the way he normally would. The guys were being laid out, even though they had tourniquets, we needed to get them out and into the helicopter.

So he got down on his chest in this dirt field that had been plowed and started swimming through the field like, like a breaststroke, moving all the dirt in front of his face with his arms, thinking that if he could, I guess ideally feel the pressure plate with his hands, going from the side, rather than applying the weight down onto it. But if you triggered it, one of these would blow his head off. He swam to one marine and we followed behind and dragged him out. And then he swam to the other marine, feeling his way there with his hands rather than with the metal detector and probe. Quickly we dragged him out, and both Marines lived. But if Staff Sergeant hadn’t done that, at least one of them would have died, because either we would have done what we were trained to do, or would have just run out of there. We didn’t have time to make that decision, because he took action and got on his chest. Both of those guys lived. It was a pretty impressive act of selflessness. So I got to see a lot of things like that on a daily basis: pretty astounding acts.

The only other big event was when we got in a big firefight on December 20. We did an ambush. It’s unclear how many guys we got. Somewhere between 13 and 17 enemy KIAs. That became pretty kinetic. My second platoon sergeant, Gonzalez, was shot between his chest and shoulder, just off the SAPI plate. He was pretty funny about it. He was convinced that no ordinary Taliban could have shot him, it was definitely a school trained sniper. We couldn’t evacuate him for four or five hours. When they hear “gunshot wound” even though he was in no danger. That’s automatically urgent and they push a helicopter to you. We were getting much better at engagement. The Taliban did not know where we were, which was spread out through all these compounds in fixed positions. They forced the helicopter in, it got hit pretty hard by a PKM, and it flew off. He had to wait till we could get vehicles there that night. But other than Staff Sergeant Gonzales being wounded, it was a very successful ambush.

I was incredibly fortunate. I always had really good marines around me, whether they were staff NCOs, the sergeants, or even our battalion commander, and company commanders. I never felt like anyone was doing anything but enabling me and the Marines to be successful. The theme of my time in the Marine Corps is that I was privileged to observe some really amazing things done by some really amazing people. I know that’s not a typical experience.

There are bad apples and bad experiences. But we came out proud of what we’d done, having gone into the heat of conflict. Proud of the Marines, proud of each other, proud of our tactics and courage. And that will be with me for the rest of my life.