Ashley Warthen

24” x 12” • Mixed Media on paper

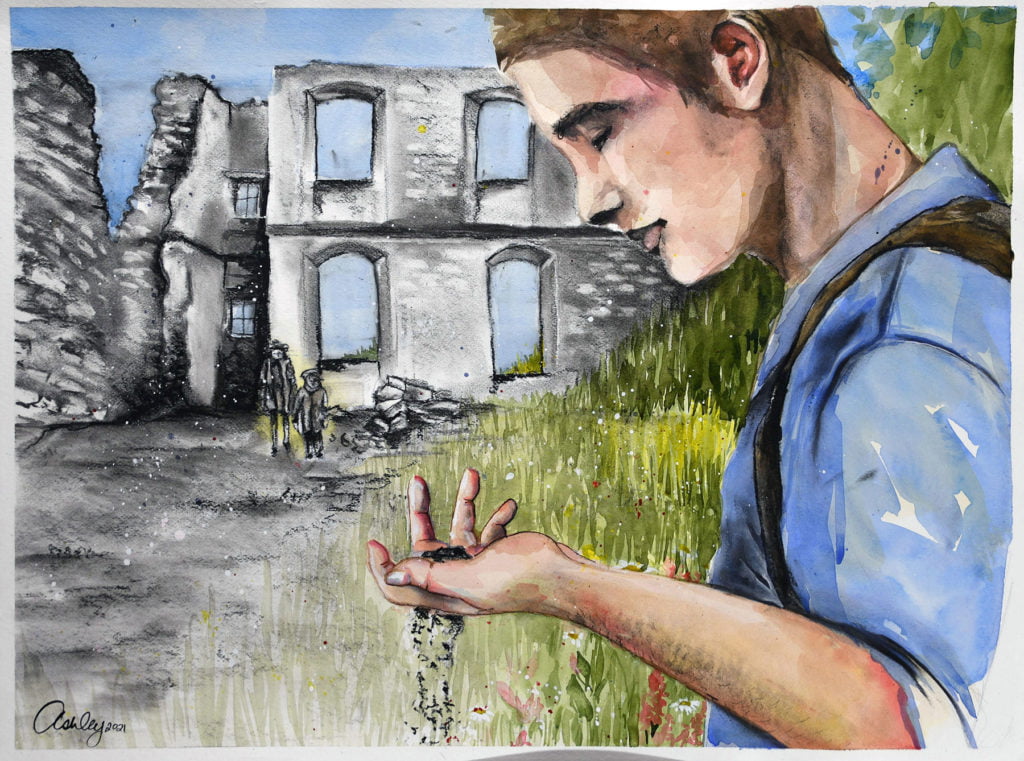

What struck me most about Ruben Jager’s story from his youth – the image that lingered in my head – was the contrast between the life and color of nature as he roamed through the French wilderness toward the mountains, with vibrant visions of swallowtails and lavender fields, versus the dark, gray chalky remnants of history that almost quite literally crumbled between his fingers.

Blending media like the textured, dry charcoals and charcoal powder with more vibrant acrylic inks and water was necessary to illustrate that the beauty of life as we know it has only grown out of those ruins. Flowers can root through the ashes and become beautiful again. And in that moment of realization, as the ancestors keep an eye on him from a distance, while holding the remnants of a skull too small to make sense, a young man became a blend of a memory of a horrific past and a symbol of hope for a brighter future.

Ashley Warthen is a portrait artist, arts librarian and published illustrator from Columbia, SC who is known for her splashy, vibrant acrylic ink paintings of animals and people. Ashley enjoys mixing media and trying new techniques, which allows her style to evolve naturally. Though her figurative work often explores aspects of the female experience, she is drawn to storytelling through the art of picture books for children.

Inspired by the experiences of Ruben Jager

Memento

by Ruben Jager

Peeping out from behind a bend in the crumbling strata of marl and chalk that formed the shocking heights and depressions of the arid landscape were the remains of something man-made. A ruin. The vestiges of a devastated world, hugging the mountainside.

*

I was seventeen at the time. Seventeen years young, and if I was indeed a man, I was the only person to know it. Having finished with high school – and by my own proclamation, with pre-adolescence – I set about exploring the world. Or rather, exploring my own capability of traversing it as I pleased, a celebration of my independence. As the coming-of-age cliché demanded, this took the form of a solitary journey into something that resembled wilderness, insofar this could be found in the Alpine regions of southeastern France. To a Dutch boy who had never known more verticality in the land than the artificial barrier his ancestors had thrown up to guard their neat lattice of perfectly flat meadows and villages from the wiles of the ocean, those mountains epitomized wilderness. After hitchhiking for a week or so I left the ‘autoroute de soleil’ behind me, along with the more populous urban areas that it strung together like pearls on a rivière. Having sampled the pleasures of these cities, I was more than satiated by the wonders of architecture, cuisine, and intoxicated nightlife that they had to offer. I held out my thumb once again, donned my most disarming smile, and when a driver finally stopped, they asked whether I was heading towards Marseille, Avignon, or some other gem of the Mediterranean. I shook my head and replied: “Est. Dans les montagnes.”

It wasn’t long before I saw the mountains rising up before me, jutting from the rolling hills like the ruined structures of some antediluvian race of long-forgotten giants. Massive domes, cathedrals, and arcades in shades of ochre, girded and crowned by viridian evergreens. It was the end of the world, or at least of the one I was familiar with. The ominously nicknamed river Rhône lay behind me, with the Alps stretching their long fingers towards it from east to west.

The valleys in between these fingers had been carved out over the course of millennia by countless tributaries of “the furious bull,” and were strewn with little villages that nestled on the arable soil between riverlet and rock face. As I’d hoped, their profusion made it unnecessary to hitch any further rides. I could simply trek along a river or cross a mountain pass into the next valley, the people of which would invariably claim that their vintages were superior to those of the previous one. To my uncultured tongue, they all tasted excellent.

Whenever I sought to take a break from the ceaseless traipsing, I’d spend a few days here and there. In late summer, it wasn’t difficult to find a few days’ work picking fruit or removing weeds from orchards. One time I spent the greater part of an afternoon helping a farmer’s sons muck out a stable, learning a number of words in the process that they hadn’t taught me in French class. In return for the sweat of my sunburnt brow, I was given ample amounts of bread, sausage, olives, and cheese to eat, wine to wash it down with, and a field to pitch my tent in. After one such stay, having mucked and munched to my heart’s content, I set off again in the early morning, resolved to cross the colossal ridge which cradled that sylvan gorge. The dry air was perfumed with lavender and the thyme crunching beneath my sandals as I set foot on the trail towards its peak.

The trail was clearly marked and well-maintained, and I was glad for the peace of mind this brought me. That day’s hike was to be one of my more ambitious ones, and it wouldn’t be the first time that a rockslide had blocked my path some halfway through the climb, forcing a return. It appeared as though such obstacles would not likely be encountered here unannounced, so I trod on without concern. After the hard work that had filled the previous few days, interspersed by intense moments of social interaction, I enjoyed my solitude and took my time.

Life, both old and new, was so utterly abundant here that it brought me to pause almost once every ten steps. Swallowtails, Apollo butterflies, Blues and Hawk-moths swarmed all around. These creatures gathered by little creeks that came forth from a cleft in the rocks and disappeared down another. There were praying mantises cunningly hidden between flowers, and, after turning over a few rocks, I found a small golden scorpion, waving its tail menacingly upon being disturbed. All the while, I was pocketing small mementos in the form of fossils and particularly nice-looking pieces of calcite, to the point that my backpack grew heavier despite the fact that my supply of water was rapidly shrinking.

Now you must know that this collector’s mania is a big part of my personality and that I have always surrounded myself with the spoils of adventures, with stories written in ink and bone, bark and mineral. All comprise a library of histories that are at once both small and great in nature. There are some objects in this world that are quite simply magical, the majority becoming so through the act of unearthing them. The ammonite that I then held in my hand whilst standing on this precipitous ridge became a testament not only to its own hundred-million-year-old origin and the fact that these mountains were once a seabed, but also to the moment at which my eyes became the first to witness it, on this journey, at the age of seventeen. Into the backpack these treasures go and onwards I walk, a long road yet ahead of me.

The sun had travelled beyond its zenith by the time I glimpsed ahead of me the sign reading the maximum altitude of the pass; I had reached the top of the trail. Exhilaration and exhaustion quickly subsided, however, when I noted a sheer rise yet ahead of me. Still, the view from up there promised to be amazing, and I clambered atop some immense boulders, and, after a glorious half-hour of euphoria at the dizzying abyss that surrounded me, I clambered back down the other side. There seemed to be an old trail there and, feeling invincible, I was curious as to where it led. As I descended the path, it grew wider and even began showing signs of what had once been pavement, shattered as though the weathered slabs of rock now were. The road curved, and I continued to follow it.

*

I had come across many ruins over the course of my journey, but I had not expected one there, hidden in the shadow of the peak I had just conquered. Most ruins were found in places where villages still stood, in the valleys, as the same reasons that had compelled people to settle there once still applied today — the presence of water and soil. Contemplating this, I basked in the surreal image that lay before me for a moment before continuing. A thunderous chorus of cicadas announced my arrival, and as I walked underneath a solitary arch not much taller than myself, I saw spiders darting away towards crevices where their crustacean ancestors had once scuttled. The walls, columns, and archways surrounding me were largely collapsed, and no roofs remained. It became clear that this place had not been a village, for it was too small to be called such, although I did come across a lavoir in the middle of it all. These consisted of smooth slabs of rock, slightly tilted towards a central basin that was fed by a stream and served as a place for washing clothes. Its presence indicated that more than one family had lived here, and as I pocketed an eroded shard of pottery, I imagined women gossiping over the sounds of murmuring water and cloth slapping against rock. The basin was cracked and bone-dry, but as I peered down the collapsed well nearby, I could hear a faint susurrus echoing from deep below the debris that blocked its entrance. At once, I became wonderfully aware of the fact that water had been at work for God knows how long to carve a path into the heart of the mountain, and I felt appreciation for such a masterful display of its stubbornness. The moment’s consideration was cut short by a sudden pang of anxiety at the idea of some lovecraftian darkness existing just beneath my feet, and I quickly walked on.

I roamed and examined some more, ate some bread and sausage in the shadow of a wall that still stood mostly upright, and approached the end of the dead little hamlet. Some twenty feet of rocky soil lay between the last of the collapsed buildings and the striated rock face. I picked up a shard of bone from the dust, brittle and bleached by the sun. Looking around, I noticed that the ground was peppered with such fragments. Some animal perished there, and its remains had been scattered by the elements. Naturally, I set about collecting them, and the aim of identification came only as an afterthought. Having collected some twenty pieces of varying size, I sat down again in that shaded spot to inspect my haul. Most fragments were splintered to the point of complete obscurity, but one was most definitely the top part of a femur with the large ball head intact. A nice find, which told me that it must have been a large mammal, maybe a deer. I put it down and picked up a curved piece, somewhat round and about four inches long. I turned it over in my hands. I saw that the edges were serrated and that the concave interior was flaking. It was perforated by a single hole the size of a dime, around which radiated a web of fractures.

Turning it back to its convex side, I noted how the smooth surface ended in a slight ridge. A ridge cradling the remains of an eye socket.

The sudden recognition of humanity in this lifeless object struck me hard. I felt my heart pounding in my chest as I deduced what answers I could about the nature of this find, and the fate of this person. The piece had undoubtedly once been the right, frontal segment of a human skull, but it was smaller, much smaller. It was definitely too small. Frantically turning the bone around, I couldn’t make sense of it. I knew how big a skull was; I had seen them for years on the shelves in biology class and numerous times in the natural history museums I loved so much. I knew this wasn’t right. I saw the perfectly round hole again, around which radiated a web of fractures. And then a realization dawned, and then another, until the threads of history wove together with the threads of the present into some sick tapestry that left me reeling.

As I left the ruins behind and made my way back to the trail, I was burdened with the knowledge that I had found the remains of a massacre. I knew that there had been German forces stationed in the area during the second world war; that the bones I had found had belonged to different people was certain. The femur had been an adult’s, after all. Mostly, my mind drifted to the hole, and the fate it alluded to. The ‘why’ of it eluded and frustrated me, even after the historical narrative had fallen into place and was tentatively confirmed to me by a local farmer in the next village, whom I had asked about a ruin by the old pass.

I travelled on, carrying those bones with me. The initial shock was replaced by that collector’s mania to which I referenced before. Seventeen years young, and I felt as though I had not defiled a resting place but instead paid homage to it. That this tragic event had become known through my unearthing of its remnants had kept it from the fate of oblivion, even if I was the only one to know it. By the time I got home, my library was a history richer.

Once in a while I open a drawer, unwrap a fragment of skull from the paper in which I keep it, and I look back at how the story of a seventeen-year-old boy converged with a story that played out some sixty years prior, set in a landscape that counts aeons.

*

Peeping out from behind a bend in the crumbling strata of marl and chalk that formed the shocking heights and depressions of the arid landscape were the remains of something man-made. A ruin. The vestiges of a devastated world, hugging the mountainside.