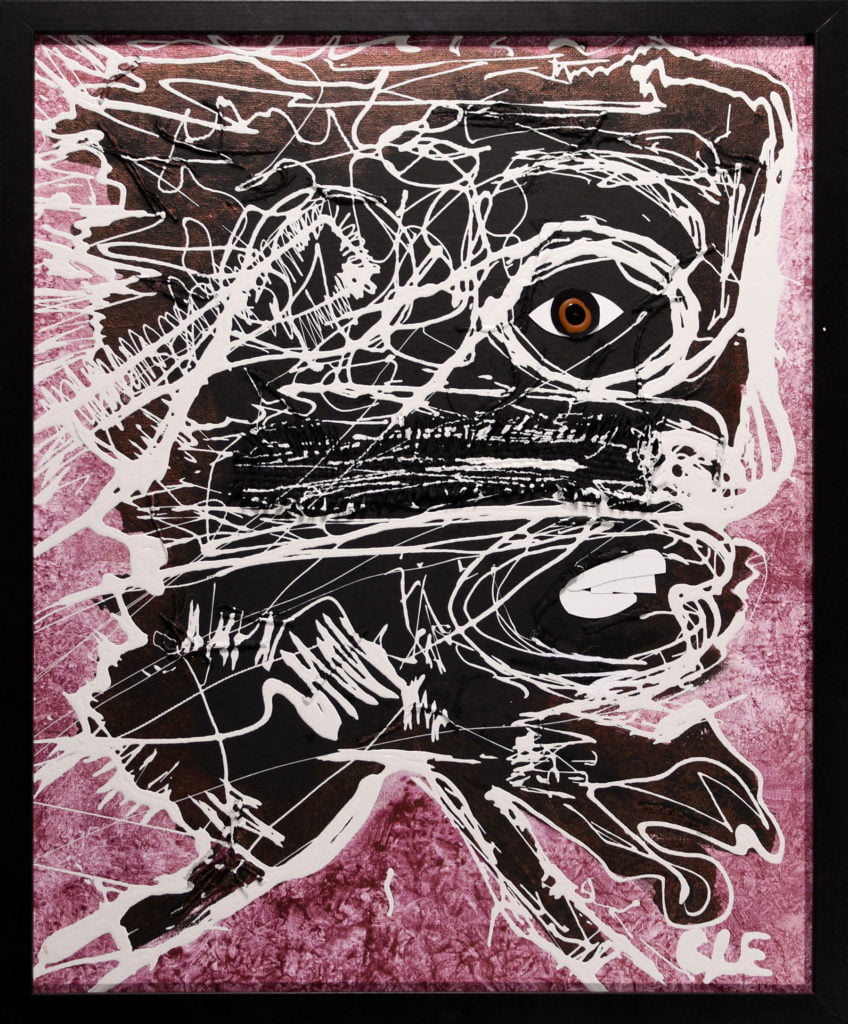

Cleaster Cotton

16” x 20” • Mixed Media Painting on Canvas

“Life has been generous with trauma and tribulations. PTSD is no stranger to me.” Cleaster Cotton (2021)

This three-toothed portrait is a marker for the indescribable, larger-than-life concept and cause of a combat veteran’s post trauma stress disorder, known as PTSD. The contrasts and textural noise within this composition represent the intrusive, invasive characteristics of PTSD. This painting was created to be a safe physical container where ‘you’ can witness, transform, transmute and defuse chaos. It serves to remind you to, “lay your burdens down.”

Inspired by the experiences of an anonymous veteran

Missing Tooth

by Robert LeHeup

“Battle not with Monsters, lest you become a Monster. And when you gaze into the Abyss, the Abyss gazes also unto you.”

-Friedrich Nietzsche

I did my best. Always have. That’s what so many of us do when we’re raised with the understanding that we’ll never be good enough. That we’ll always fall short, regardless of tears shed or blood spilled. Fight hard, love deeply, because no one else thinks you’re worthy enough to fight for or to love. And those things for which we fight are never for us. They’re to protect and support others. We fight cold ideas that undermine the ‘Good’ in us. We fight bullies. We fight injustice because we know what it’s like for others to stand by, to watch, to crack jokes as we are dehumanized, debased, and suffer beyond measure. We are the protectors of those we love, our polarized kindness, our eagerness to sacrifice ourselves, held white-kuckled by the antithetic consequence of our boundless rage. That’s why I joined the Marine Corps infantry in the first place.

In time, and with a wild abandonment of my own soul, I dove into the idea of becoming the righteous warrior, sowing the seeds of my own morality to plant long into the future. To be on the side of angels, if for no other reason than to get a pat on the head when I tore apart demons with my teeth. This didn’t make me socially acceptable in the “real world,” but it lined up perfectly with being a Marine. The Bad Guys weren’t just defined. They were universally understood. They needed killing, often in creative ways, because they wanted to do even worse at any given time. This would be further underscored by our common will to do ‘Good’. After all, we’re the protectors.

Of course, that isn’t always the case. Once the depth of homicidal tendencies are cooked into you, it takes a certain discipline to know what’s right and wrong. And so I would teach those who were under my charge to seek a balance between our duty of violence and our necessary humanity. I would have them read “If,” by Rudyard Kipling. I would whisper to them through clenched teeth “You’re better than this” whenever I punished them by bringing them to fiery pain and brutal collapse. I tried to be kind when I could afford it. And when it wasn’t affordable, I was of such viciousness that every aspect of who I was might as well have been drenched in blood and offal, laughing hysterically at all things sacred.

“Yes, you might have to kill children.”

“No, we will never fight a country that upholds the Geneva Convention, so here’s ways around it…”

When you doubt your own validity, sometimes leaning into your perspective is the only option you have. Fast forward to Afghanistan, where I had been put in charge of three other Marines to guard different posts. And what’s more, we were working with Afghans from the city who were helping us with many of these posts. One in particular was at a second gate into the compound, the first being part of a massive, barbed wire wall at the actual entrance. The second was a wrought iron monstrosity of a thing, heavy in both weight and significance, ensuring that anyone wishing harm on the compound would be trapped between a rock and… well… a massive wrought iron gate.

I remember when I was first introduced to him. To Tooth. We called him that because he only had three in his head, the rest lost to time, poor hygiene, and Kaht, a green plant they used that has similar effects to cocaine without the illegality. He seemed like a kind man, never shying away from showing off all three of those teeth like a proud child whose report card was magnetized to the refrigerator. He could also blow us up, if we weren’t careful. The platoon commander, wearing full combat gear, nodded his head in Tooth’s direction.

“This is Tooth,” he said. “Don’t kill him.”

I stared at Tooth like I expected him to blow us up at any minute.

“No promises,” I said, smiling in a way that was more baring teeth than showing pleasure at a circumstance. He was a Bad Guy, after all. Or at least, you couldn’t tell him apart from one.

It took about a month of us working together, moving this massive gate back and forth, pouring pitch-black oil over wood to start fires in a burn barrel in order to stay warm in the biting cold, and generally hating life in the best ways, before I began opening up to him. It took other Marines far less time, but having so much anger in your soul can make you adamant. Patient. Eager to be proven right that you can’t trust anyone. But after that month, it snowballed.

Two or three weeks later, we were greeting one another in the customary way of Afghanistan.

“Chithoorasti. Hoobasti. Jarnajooras.”

“Hoobastom. Toshakoor. Zindabashi.”

Then we would try to have a conversation with one another through broken words and gestures. I would try to tell him how the previous 12 hours had gone and he, presumably, would do the same. But he didn’t speak English and I didn’t speak Dari, so about 5 minutes after trying to get simple things across, we both burst into laughter at the ridiculous nature of where we found ourselves.

Here we were, from entirely different sides of the world, not being able to speak with one another, forced into a reality where my brothers were looking to kill his… and it was wonderful. It was as though the best parts of what I saw in people were laid out in repeated circumstances that I couldn’t have imagined. It was the sort of thing worth fighting for. It was the sort of thing worth protecting. And we went on further adventures as well.

I was paying him a relative fortune for him to go out in town and get us pistachios. I mean to say that I paid him what would take most Afghans half a year to make, but what people in the US would call slightly more than one hour of minimum wage. Roughly $10 for the amount of pistachios that would cost $30 back home, all the more valuable because of the endearing nature of the experience. Every tenth pistachio tasted like the monkey cages at the zoo smell, and so, given the infantry’s love of misery, it was like a twisted, darkly wonderful Christmas.

A couple of months later, I went out on post to relieve the Marine I had trained before. One of the ones for whom I was responsible. I don’t remember much about it, except that it was an entirely normal morning, air crisp, breath visible, nose burning from the cold. The sun was rising and I was expecting pistachios. But when I got there, Tooth wasn’t there to greet me.

I asked with my typical brusqueness, eyebrows curled with murderous impatience, teeth flashing white, “Where the fuck’s Tooth?”

It was then that the Marine approached me. The one I had known for over a year, who I had trained in detail on the art of moral flexibility and calculated cruelty whenever it was necessary. He clapped me on my back, smiling, a comrade greeting another as though getting the news his wife was pregnant.

“I force-fed him oil! He ain’t coming back!”

His laughter was thunderous. The sort you’d imagine from a victorious jarl, fresh from battle, toasting his servants and groping his queen in a drunken stupor. I wanted to kill him immediately. But I didn’t. Because you can’t. At least, not in the open. Not if you wanted to stay alive yourself and remain combat effective. Not if you wanted our mission accomplished with the efficiency Marines are known to possess. Especially if all he had to do was say “No. I did not do that.” Case closed.

All I could do was stare at him. After all, as much as anything else, he’d done this to impress me.

And so I worked out to where my heartbeat was in the mid 170s for an hour at a time, became less patient, less understanding, less human than I had planned to be once I got out. “They” were right. Those people who had taught and raised me to believe that I wasn’t good enough in spite of all my efforts, in spite of my kind, generous intentions and the many heartbreaks that followed, could now look at me and say “Told ya.” And that’s when the suicidal thoughts really started kicking in.

I hated myself. Hated the world for not allowing me a moment’s grace for all my hard work and sacrifice. Hated those that cheered me on with the empty head-nod of “Thank you for your service,” as though they already knew my story to a point that they didn’t even need to hear it. And I brought that hate and bitterness through most of my adulthood, fed by the stark reality that a statute of limitations left me incapable of action.

After years of counseling, I had resigned myself to the idea that I had not, in fact, killed Tooth. That it was someone who was already rotten, having joined for the exact opposite reasons why I had, fighting right next to me. He was the physical incarnation of the idea that there isn’t enough ‘Good’ in us. That you’re a bully or you get bullied. That kindness and understanding were stupid, pointless endeavors that were laughable at best, and at worst, worth killing to undermine. But with enough help, I was able to grow beyond my own suffering and guilt, continuing to strive to be the best person I could for those that I loved. That love, in all its forms, is worth fighting for. I did my best. And with support, I’ve succeeded.