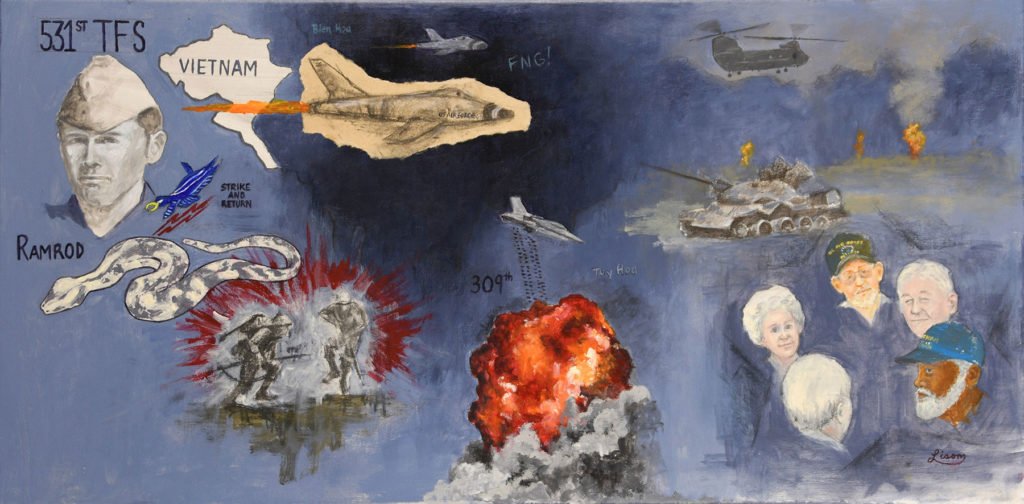

Lori Isom

12” x 24” • Acrylic, Charcoal, and Collage on Canvas

My deep desire as an artist is to present my subject in the most honest and sincere way. Like any artist, I wasnt the viewer to feel the emotion behind the painting, not just see a pretty picture. I am stimulated by interesting composition, structure, and color usage when contemplating a painting. However, emotion is really what drives me.

Inspired by the experiences of Alton Whitley

SCRAMBLE TWO RAMRODS

by Alton Whitley

It was the spring of 1970. I had just completed a post flight debriefing following a close air support mission in the F-100 Supersabre with the 531st Tactical Fighter Squadron (TFS) at Bien Hoa Airbase, Vietnam. The 531st TFS was known as the “Ramrods.” It was both our unit call sign and the name of our squadron mascot, a boa constrictor. “Ramrod” had been shipped to his new home at the Salt Lake City Zoo just before I arrived in country. Prior to heading to the squadron hootch, I took a final glance at the schedule for the next day and saw I was going to be on the alert pad the next night with my flight commander, Major Johnson. That was a big deal for this bright eyed and bushy tailed Lieutenant. Being certified to sit on alert at night for close air support missions was a major step in my certification as a full fledged combat fighter pilot in the F-100 Supersabre. It was a milestone I wanted to get behind me.

Until I filled this square, I was still a new guy or FNG in the eyes of the seasoned aviators in my squadron. These guys were a tight knit group. They were the old heads. They’d been there and done that. All of them loved to have fun with the new Lieutenants or LTs. They were all experienced in the F-100 and seldom passed up on the opportunity to challenge the five of us who had arrived together to finally rid ourselves of the much dreaded FNG label.

Our in-country checkout in the F-100 involved more than we had originally anticipated. But we were fortunate. These old heads were all great mentors. Yeah, they were arrogant, salty, tough and demanding of us, but we knew we had to earn their trust and respect. The were determined to teach us every lesson they had learned so we could do our job in both a safe and lethal manner. By safe, I mean we wouldn’t bust our butts and destroy a perfectly good airplane because we flew it outside of its intended flight envelope, or do something stupid like trying to defy the laws of physics. By lethal, I mean we had to demonstrate we could put our bombs, napalm and 20 millimeter strafe precisely on the intended target while minimizing our exposure to any threat. All the munitions we employed were deadly and we took the greatest precaution to avoid friendly fire, for it was perhaps the greatest sin of all.

The LTs knew respect would come with genuine trust. Our mentors wanted us to do what we were supposed to do in the manner we were expected to do it. No two missions were ever the same. The weather, the threat and the situation on the ground were constantly changing. Our mentors were preparing us to deal with both adversity and the unexpected. In the F-100 we seemed to have more than our share of both. Many of these seasoned combat aviators had spent a lot of their time in the F-100 sitting nuclear alert, preparing for a one way trip to drop a single nuke somewhere in the Soviet Union. When the war started in the jungles of Vietnam, a lot of what they were teaching us was learned the hard way with the loss of talented and patriotic aviators and perfectly good airplanes. They did not want us to repeat the mistakes that had cost so many others their lives. We had no choice but to trust them and we wanted them to trust us.

The old heads didn’t want us to become a statistic. Not because they had taken a liking to us or because we had become close to them. They simply didn’t want to go through the trouble of gathering, packing and sending our stuff to a grieving wife, children or parents of a fighter pilot lost. They knew snotty nosed Lieutenants were both naive and dangerous. It was easier on them if they just kept us alive by teaching us the ropes than it was to take care of the duties and requirements as a result of our demise.

To prepare for alert duty the next night, I intended to sleep in a little the following morning. I had a couple of beers at the squadron bar that night thinking that would help me sleep in later than normal. I still woke up at my usual time the next morning and had accomplished little in my effort to adjust my sleep cycle for my night alert duty. While my anticipation started to build, I had flown an uneventful night mission a couple of days prior, so I felt semi-comfortable with the task at hand. However, sitting on the alert pad was different. I knew if and when the alert pad klaxon went off, I had to be up and out the door with all my gear on within a matter of minutes. Night flying alone can be scary. Flying combat close air support at night is inherently dangerous for everyone involved with the mission.

Your depth perception, bad weather, cockpit lighting and vertigo can all play tricks on your mind, especially at night. The F-100 cockpit lighting for night flying was a total mess. The panels, gauges and instruments often had inconsistent levels of illumination. Some of the armament switches were hard to see and manage in the heat of battle, especially at night. Individually, none of these were a big deal. Dealing with all of these issues at night in a dynamic situation could easily lead to disorientation or confusion that could prove deadly. None of that really seemed to matter at the time for I thought I was an invincible fighter pilot; and I thought there was nothing I couldn’t do. I did not feel that way 20 years later when I flew America’s first stealth fighter over Baghdad the first night of Desert Storm. Age, experience, the loss of fellow aviators, marriage and fatherhood will do that to you. But that is another story for another time.

My first night on the alert pad started well before sunset. Major Johnson and I arrived a little early to walk through the facility, review alert pad procedures; and do our customary walk around preflight check of our airplane and ordnance. I had some chow and retired to my bunk with my flight suit and boots on, anxiously awaiting the call of the klaxon. A couple of hours later, the inevitable call for “HELP” came without any warning. 7th Air Force Headquarters at Tan Son Nhut Airbase near Saigon was scrambling two F-100 RAMRODs from the 531st TFS at Bien Hoa to help a unit in a bind in III Corps. The initial blast of the klaxon startled me. While everyone hustled about the alert pad taking care of their assigned duties, I hesitated momentarily but quickly got it together, gathered a few items and out the door I went. After a quick glance at my aircraft, I was up the ladder of my single seat jet and crawled into the cockpit. The crew chief followed me up the ladder and made sure I was buckled into my parachute and strapped into the ejection seat. We started engines, checked in on the radio, requested taxi instructions and headed to the last chance area. That’s where a small maintenance crew and some armament guys gave us a final check of our aircraft and ordnance before we pulled onto the runway. In the cockpit I only had to remember one pin before we pulled onto the runway – my ejection seat pin. Overlooking that little pin could cost your life if you failed to remove it.

After we were cleared for takeoff, we pulled onto the runway in formation, held the brakes and ran up our engines to full power. Major Johnson simultaneously released his brakes as he lit the afterburner of his Pratt and Whitney J-57 engine. A long orange plume of fire stretched far out of the back of his airplane as he rolled down the runway. I followed him 15 – 20 seconds later. Our noisy departure surely upset some troops trying to get some shut eye, but it meant help was on the way for some friendly troops on the ground. I found my leader in the darkness of the night and joined up with him as we headed south to the target area. I recall the mission took us somewhere in the southern part of III Corps and that things worked pretty much as planned.

We released our flares over the glowing log flare the Forward Air Controller or FAC had put down to mark the general target area. We delivered our ordnance, making corrections as directed by the FAC. Fortunately, the weather was good that night and neither of us had any battle damage from the light, sporadic ground fire we encountered. We had a routine trip home that ended with a good drag chute for both of us on landing. If the F-100 drag chute failed to deploy on landing, you’d be glad you flew final approach at the proper speed or you just might end up in the barrier at the departure end of the runway, especially on a wet runway. The alternative was hot brakes, blown tires and a likely wheel fire due to severed hydraulic lines. If any of this happened, it would be difficult to shed the FNG label.

Missions off the alert pad were rarely routine. By their nature these missions are in response to a dire need of immediate air support. Normally we arrived in the target area, our FAC would be dealing with a “troops in contact” situation. Anytime our troops were in close proximity to the enemy, we had to take special care to avoid friendly fire. This got a little hairy when the friendlies were screaming at the FAC for help, yet it was almost impossible to distinguish definitive lines between the good guys and the bad guys.

Fortunately, I survived my first and many more night missions off of the alert pad during my first tour. While I was at Bien Hoa almost all of my night missions were to III and IV corps where the terrain is mostly flat. That changed about halfway through my tour when the F-100s were moved out of Bien Hoa. I transferred to Tuy Hoa Airbase along the coast in II Corps where I was assigned to the 309th TFS “Wild Ducks.” Night missions there were usually of a different nature because of the high terrain to the west of our location.

The F-100 was the workhorse of close air support in Vietnam, flying over 360,000 combat sorties. I will never forget those night missions where vertigo, disorientation and the fog of war were potential grim reapers. I never really became complacent, for the occasional loss of pilots and aircraft, aircraft damage, muzzle flashes and tracers were a constant reminder that my job was to break things and kill people who were trying to kill me. I was fortunate to survive my first tour. As if the dangers of flying combat sorties at night were not enough, we could never really let our guard down because of the random 122 mm rockets impacting our air patches, especially when I was at Bien Hoa.

Those memorable night missions under the light of flares attached to a small parachute never failed to generate a flow of adrenaline. When we were young we all did some wild and crazy things without knowing or appreciating how dangerous it was at the time. Most of us only realized it well after the fact. I can only imagine how scary it must have been on the ground for those near our bomb impacts, our splashes of napalm and our well intended strafing from four 20 mike mike guns at an enemy closing in on friendly forces. I will never forget that first night mission off the alert pad, when two RAMRODS were scrambled to help some ground troops in the spring of 1970. Shortly after that, I was no longer considered an FNG.

Two years after my first tour, I returned to the war flying the much more sophisticated A-7D Corsair assigned to the 3rd TFS, a search and rescue unit stationed in Thailand. Because the war was winding down, we ended primarily flying close air support as well as river and convoy escort missions in Cambodia. What I could never have imagined though was that over 20 years later, I would be flying America’s first stealth fighter, the F-117, and commanding another generation of FNGs when they found themselves in the skies of Iraq on the first night of Desert Storm. As we dropped our laser guided bombs in the stunning barrage of anti aircraft artillery and surface to air missiles we encountered, I once again felt that same rush of adrenaline. I had experienced this same feeling on that first night mission off the alert pad in Vietnam. Fortunately, American ingenuity and stealth technology allowed us to make precision strikes with sophisticated weapons despite horrific enemy air defenses. What mattered most in Vietnam was we had helped someone on the ground we will never know. In Desert Storm, our success in taking out our assigned strategic targets accelerated the defeat of a once formidable Iraq military and ultimately saved the lives of many on the ground.

Now 50 years later, when I meet weekly with my Healing Group of other veterans, the majority of which are Army or Marine veterans of Vietnam, I realize one of them could have easily been on the ground that night in the spring of 1970 when I flew that first night mission off of the alert pad. Our group has no heroes. But we all were warriors doing our duty. Everyone, regardless of their service or specialty, gave something to this war. We all had friends and comrades who gave it everything. Many of us left our youthful innocence and part of our heart and soul in that ungodly and unforgiving place called Vietnam. This Healing Group and another group of former warriors known as “Brothers and Sisters Like These” have helped us all put to rest events and memories that have kept some off balance for decades since we saw combat. We are blessed to have found one another.

Alton Whitley

F-100 Pilot, Vietnam, 1970