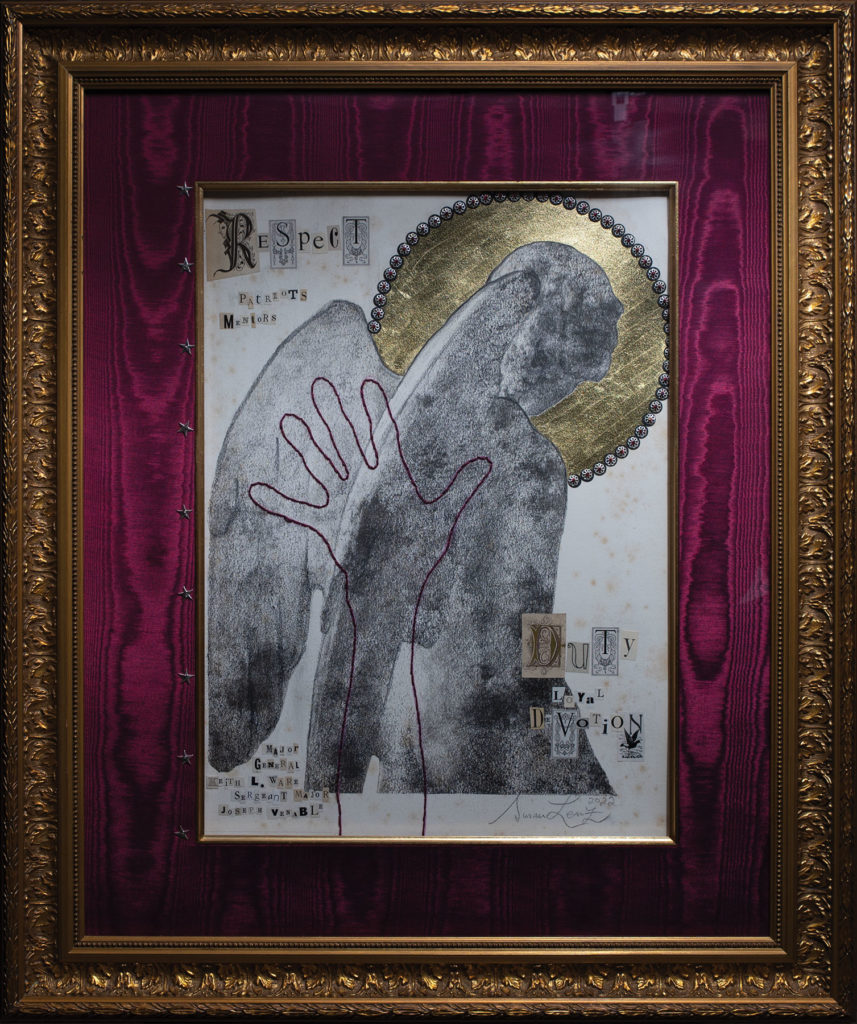

Susan Lenz

29″ x 35″ • Mixed Media

Artist Statement

In 1981, undergraduate Maya Lin (just 21 years old) won the public design competition for Vietnam Memorial. Tens of thousands have placed their hands upon that black granite, wept millions of tears, left personal tokens, and mourned. Lin’s intention was “to create an opening or a wound in the earth to symbolize the pain caused by the war and its many casualties.” I’ve walked the 246 feet of angled panels, shocked by more than 58,300 etched names, and cried. Yet, I didn’t know any of the soldiers. After reading this essay, I feel like I now know two of them. And like the author who is still contemplating life’s mysteries, I am grateful to share their honorable story.

Facebook: susan.lenz

Instagram: @susanlenz

by Lou Christine

Major-General Keith L. Ware and Sergeant-Major Joseph A Venable became mentors of mine back at Fort Hood, Texas in 1967. Despite their common cause both men’s professional and personal demeanors couldn’t have been more different.

General Ware came across more like a college professor in rimless glasses or a CEO for a Fortune 500 company. His uniform’s fatigues were soft rather than starched. He looked dour rather than dashing. He loped rather than marched; he was as unmilitary looking as a General could. On the other hand, Sergeant Major Venable was a soldier’s soldier, ruggedly handsome, ramrod straight, lean, swagger stick in hand whose language was tough and often vulgar while peppered with snippets of Army jargon.

Ware spoke eloquently in a soft tone like a refined New Englander. As for Venable he was all about giving and taking orders as he barked with a no-nonsense, Cajun, Law-siana drawl.

General Ware was drafted in 1938. He became the first Officer Candidate School graduate to reach the rank of General and the last Mustang General, meaning he went from a private to become one of the nation’s most decorated and diverse, high-ranking officers. Sergeant Major Venable stemmed from the bayou country of Louisiana, drawn into the Army during WWII. Both served in the South of France during the big war.

Ware distinguished himself on the battlefield in France. For a defining heroic effort, he won the Congressional Medal of Honor, the nation’s highest military honor.

“Commanding the 1st Battalion, 15th Infantry, attacking a strongly held enemy position on a hill near Sigolsheim, France, on 26 December 1944, found that one of his assault companies had been stopped and forced to dig in by a concentration of enemy artillery, mortar, and machinegun fire. The company suffered casualties in attempting to take the hill. Realizing his men must be inspired Lt. Col. Ware went forward 150 yards beyond the most forward elements of his command, and for two hours reconnoitered the enemy positions, deliberately drawing fire that caused the enemy to disclose their fortifications. Returning to his company, he armed himself with an automatic rifle and boldly advanced towards the enemy, followed by two officers, nine enlisted men, and a tank.

Approaching an enemy machinegun, Ware shot two German riflemen and fired tracers into the emplacement, indicating its position to his tank, which promptly knocked the gun out of action. Ware then turned his attention to a second machine gun, killing two of its supporting riflemen and forcing the others to surrender. The tank destroyed the gun. Having expended the ammunition for the automatic rifle, Lt. Col. Ware armed with an Ml rifle, killed a German rifleman, and fired upon a third machinegun 50 yards away. His tank silenced the gun. Upon his approach to a fourth machinegun, its supporting riflemen surrendered, and his tank disposed of the gun. During this action, Lt. Col. Ware was wounded three times but refused medical attention until this important hill position was cleared of the enemy and securely occupied by his command.”

Earlier in the war Keith Ware commanded the famous Audey Murphy. Within the pages of Murphy’s best-selling memoir, “To Hell and Back,” Murphy recounted how he tagged along as Ware led a patrol behind enemy lines. In that action Murphy saved Ware’s life by knocking off an enemy who had Ware in his sights. That action bonded the two men over a lifetime and earned Murphy his first Silver Star. He went on to become a Congressional Medal of Honor recipient, then a celebrity and movie star. Unassumingly Ware continued his military career.

Ware again served with honor in Korea earning additional citations for his valor and leadership. He continued the academic portion of his career while still in uniform. He attended and later taught at the Army’s War College in Carlisle, Pennsylvania. He became the Army’s liaison to the United States Congress. He wrote manuals on tactical nuclear warfare respected on both sides of the Iron Curtain. He became the Army’s Chief in Public Affairs and today; the Keith L. Ware Award is annually bestowed on the Army’s top journalist. Back in 1966, as a draftee, I lucked out and was assigned to 3rd Corps Headquarters as the custodian of classified documents for the Corps’ Command Section.

On my first day I was to report to Fort Hood’s Sergeant Major the top kick of all top kicks on post. Sergeant Major Joseph Venable snarled at me. His tone wasn’t flattering toward a then lowly PFC.

“Boy!” he yelped, “I work for one man, the Commanding General of the 3rd Corps, and you now work for me! Captains, Majors and Colonels around here are a dime a dozen, and they mean nothing to me other than the military courtesy they are due. From now on you are ED, exempt from roll calls, KP, guard duty, CQ, inspections and all the other duties taking place around the barracks. You’ll get a fresh haircut every week and break starched fatigues daily. You show your respect to all ranked above you, but if one swinging dick gives you any crap you tell me and I’ll take care of it. For that: ‘Me and the General’ expect your total devotion to duty. You have your sorry butt in this office 7 a.m. sharp and make fresh coffee or you can go back to where you came from as a sorry-assed recon scout in the First Armor Cav. Understand that Private?”

“Yes Sergeant!”

The tough talking Sergeant Major kept his word. From then on, and without doubt, I was his boy. The duty was choice. I learned firsthand about how the upper echelons of the military function. My company commander and first sergeant never leaned on me because of my high-flatulent status at HHQ. I had unearned clout. Everybody on post was scared of the Sergeant Major’s power and wrath.

During my stay at Fort Hood the Army decided to create a new position, The Sergeant Major of the entire Army. Venable became runner up for the position, only to be nosed out by a Sergeant Major Woodward, who already served in Vietnam, an assignment Venable had yet to achieve. Later on Woodward was indicted for being part of a syndicate that bilked the military out of millions of dollars of supplies that the crooks sold on the black market.

Venable loved the Army. He even savored the panther-piss tasting coffee served in mess halls. His uniform was immaculate. He adored a beautiful, full-of-life wife and pretty daughters. If he’d see an overweight sergeant, he’d lock the fatso’s heels and order him to lose weight or he’d be busted down a rank or maybe even thrown out of the Army.

Over time, with me, his tone softened. We had great laughs. When I would interject or give an opinion about the Army he’d rile me and say,

“Christine, you’re nothing but Christmas help in this man’s Army, just do your job and then you can go back to your candy-ass civilian life and be somebody with all your ideas back on the block!”

Venable was instrumental at having me attain my sergeant’s stripes. He pinned them on my sleeves himself on the day of my promotion, rubbing my head like you do a toddler’s, telling me I was then a full-fledged sergeant like himself.

One highlight of our service together took place when President Johnson visited Fort Hood. In a small conference room Sergeant Major and me along with eleven General Officers braced at full attention as the Commander in Chief entered the room to be briefed on the readiness of Fort Hood troops slated for Vietnam. Rather than hobnobbing with the generals LBJ turned his attention to the Sergeant Major and myself offering astonishing small talk.

It was a few months later when then Brigadier General Ware came on the scene to become Deputy Commander of 3rd Corps. Part of my job was to go to the Adjutants General’s Office to pick up documents addressed to the Command Section. I entered the inner sanctum with a TWIX for General Ware. His Aide-de-Camp was not at his desk just outside the General’s office. I noticed Sergeant Major sitting with the General in a casual manner with his leg crossed. The General and Sergeant Major had struck up a friendship and spent much time together discussing training and other aspects of military life. When he saw me, he waved me into the General’s office.

I handed over the dispatch to the General. I remained at attention. General Ware put on his glasses and opened the dispatch. While reading it aloud he stood. He had been promoted to Major General and was to report to Vietnam for temporary duty at first and then take over the command of the 1st Infantry Division that was the Army’s buffer Division up on the DMZ separating North and South Vietnam, which was then one of the hottest combat spots on earth.

In those days to achieve higher rank it was essential to command a combat arms unit. Ware had yet to serve in Vietnam. There was a glow about the General. Right then, Sergeant Major exploded out of his chair.

“Sir, nothing would make me prouder than to serve with you as your Division’s Sergeant Major while in harm’s way!”

It was both a magnanimous and poignant moment. At the time I had 54 days left before being discharged. As a 20 year–old, all I looked forward to, was to get out, make money, buy a nice car and date beautiful women, yet something stirred inside me to volunteer. However, soon enough I came to my senses and stifled any thoughts about asking to accompany the dynamic duo.

I was discharged on January 12, 1968. Some months later while watching the news Walter Cronkite reported that the command helicopter of the Big Red One was shot down and all aboard killed including its commander, Major General Keith L. Ware.

Years later, I visited the Vietnam Memorial in Washington D.C. I possessed my own list of those I knew who perished. General Ware was on my list. I found the ebony, marble slab where Ware’s name was etched in along with the other 58,000 plus. I scanned the marble slab and was shaken and taken to my knees to see the name of Sergeant Major Joseph A. Venable posted directly next to Ware’s. I could hardly breath and was at a loss for words. He perished with his General, with him to the end!

All I could think to do was get back on my feet, close my eyes and place my hand over both those names and pay homage. Two men, two patriots, two warriors whose loyal combined duty spanned almost 60 years, wasted in one horrific moment!

I discovered some of the details how the General, his aides, the Sergeant Major and even the division mascot, a German Sheppard named King, all went down in a fiery crash near the Cambodian border on September 13th, 1968.

Like many who’ve served I’ve asked why? Why was I plucked out of the First Armored Cav., as a scout with the Americal Division that served in Pleiku, at Camp Holloway? Why did I get that choice job with the Army’s elite? What if I would have asked to go with those two warriors? The what-ifs and how-comes are part of life’s mysteries and maybe the gist of it all is so I’d be able to share their honorable story with you.