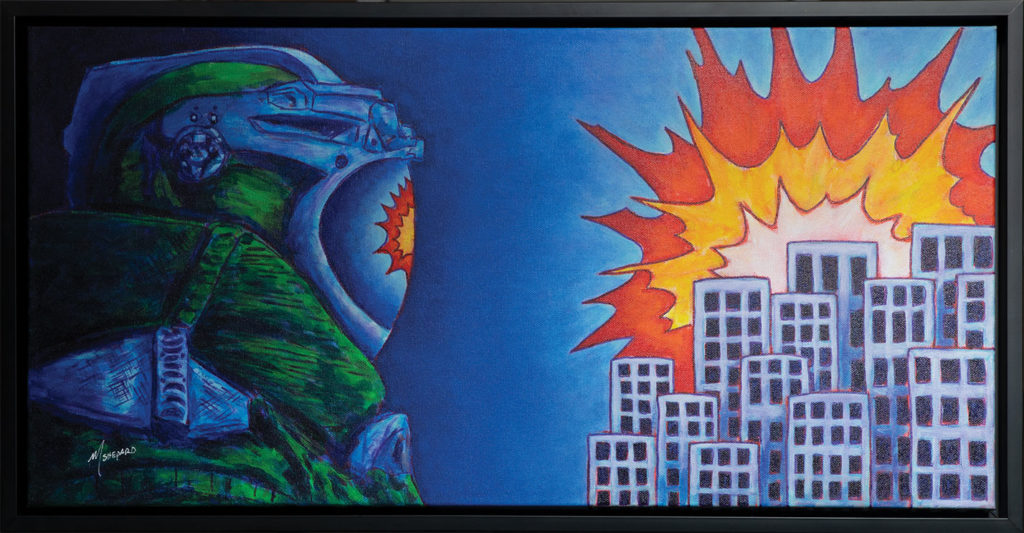

Michael Shepard

30″ x 15″ • Acrylic on Canvas

Artist Statement

When approached to paint a piece for Tony Fiteni’s story, I asked myself, “How? How can I relate and connect a piece to this story?” “I’m not military and I don’t like war, guns, loud noises, conflict, or destruction.” So, I turned to the emotional and mental aspects of military work and the havoc that could be wrought on an individual’s life: stress, trauma, fear, emotional fatigue, confusion, and anxiety to mention a few. This took me to a period of my life during 2019 when I was recovering from a severe alcohol addiction and was fighting to stay alive. I feel this time of my life could only be best described for me as living in a war zone. It is from what I experienced during period I drew the inspiration for the painting and was able to connect personally to the story.

During 2019, I was suffering with a lot of physical and mental issues relating to recovery and liver complications. I didn’t have my medication’s and was walking around aimlessly confused, stressed, exhausted, hungry and scared. My mental capacity was almost completely diminished. There were times I didn’t know if I was awake or not. It was like I was watching myself through a tunnel going through these horrible events. At times, it seemed as though nothing was quite right or even real. The whole time I felt like I was in this cartoon-esque nightmare. This is how I decided on the style for this piece to relate to Tony Fiteni’s story about being an EOD expert.

There are two halves to this painting and based on artistic elements, I tried to balance the piece to keep your eye moving back-and-forth, never leaving the canvas, in order to tell the story. The left half of the painting represents Tony dressed in his EOD gear and facing towards his daunting task of dealing with the post bombing destruction and potential life-threatening aspects of his duties. This style is somewhat illustrative, but I purposefully didn’t make the outlining perfect in order to convey this dreamlike version of reality that doesn’t seem quite right.

The background is painting from dark to light to move you from left to right and convey a tunnel like scene if you can imagine looking at an explosion head on with darkness all around. The explosion is painted to bring you back across the canvas. The lights and darks and contrasting colors were painted to create rapid movement to bounce your eyes back-and-forth throughout the painting which should subconsciously convey a sense of urgency and tension. The size of the city and explosion are painted to be symmetric with Tony’s jacket and helmet respectively to give balance to the piece.

If I succeeded, the viewer should be able to easily connect with this piece through the fun nature of the style, vivid colors, and high level of movement within The painting and appreciate the story of Tony Fiteni.

Thank you for your service.

by Susan Lenz

I.

I am The Bomb. I was born in an 11th century, Chinese bamboo tube and within the next hundred years grew into cast iron shells packed with explosive gunpowder. My reign of fear and destruction spread across the globe, and by 1849 I was dropped by unmanned Austrian balloons on Venice in the First Italian War of Independence. I come in different sizes, shapes, and make up, from compressed gas to thermobaric designs and both nuclear fission and nuclear fusion capabilities meant for massive destruction. I can incinerate objects within my blast range with temperatures approaching 4,500 degrees Fahrenheit, and my shock waves can fatally damage internal organs. Since the 14th century, I’ve shattered my own casing and spit my fill of metal shards in a technique called fragmentation. Once, I shot a two-ton anchor almost two miles inland from the Galveston Bay. That was on April 16, 1947 in an incident now known as the Texas City Disaster, the deadliest industrial accident in U.S. history. Ultimately, I killed at least 581 people including all but one member of the Texas City volunteer fire department. I am the “Father of All Bombs”, the Russian designed, explosive with 44 tons of TNT that detonates mid-air and sets off a supersonic shock wave with extremely high temperatures. I am the “Mother of All Bombs”, the Albert L. Weimorts, Jr. designed, large-yield bomb said to be the most powerful non-nuclear weapon in the American arsenal. My name comes from the Latin word “bombus”, an onomatopoetic word imitating the sound I make upon impact. I am the BOMB.

II.

I am Toni Fiteni, the bomb disposal expert. I come from a long and well established British history in the profession, one that starts with Sir Vivian Dering Majendie, a major in the Royal Artillery who first investigated the Regent’s Canal explosion of October 2, 1874. Five tons of gunpowder and six barrels of petroleum on the Tilbury barge took out the lives of all on board, the Macclesfield Bridge, and even damaged cages at the nearby zoo. Majendie framed the 1875 Explosive Act, the first modern legislation for explosive control. He pioneered many disposal techniques. Since then, England has been rightfully and fearfully invested in bomb disposal. I am part of that investment. For twenty-five years, I served in the Royal Air Force (RAF), like my father before me, like both my grandfathers before him. I guess I was destined to this line of work since I was knee high to a grasshopper.

My armament jobs took me around the world, on aircraft, in muddy London basements, through the rubble of ruined Victorian homes, and into the landfills of former military bases. I’ve been trained to seek bombs, bullets, missiles, ejection seats, and stockpiles of ammunition whether made by warring countries or as a terrorist’s IED (Improvised Explosive Device). I was at the zoo with my family when the Gulf War started. I was eager to go because of all the training. Knowledge and experience are the criteria for the lethal nature of this work. My MOS (Military Occupational Specialty) was for elite service and I was ready. There was a strong sense of purpose to this first “proper war” since WWII. Yet, I was one of the team left behind to fulfill the unit’s duty to first protect the UK’s domestic population.

I did, however, go to the Falkland Islands in 1994, long after the initial invasion and the end of the seventy-four day conflict. Yet, this was at a critical time. Argentina had just adopted a new constitution declaring the Falkland Islands as part of one of its provinces though it was and still operates as a self-governing British Overseas Territory. Anything could have happened back then. We didn’t want to be caught with our pants down again! Sending in bomb disposal teams was critical. After all, by 2011, there were still 113 uncleared minefields and any number of UXOs (Unexploded Ordnances) covering more than 3,200 acres. At the time, estimates numbered 20,000 anti-personnel mines and 5,000 anti-tank mines. It wasn’t until after the Mine Ban Treaty that the British Government finally committed to clearing the mines. The promise gave us a deadline, by the end of 2019. The last landmine was detonated during a November 2020 weekend celebration. My presence was important. I was there. I was trained, an expert in disposal in a place with altogether too many UXOs.

Despite my preparedness and willingness to serve, I wasn’t sent to Serbia either. Instead, I had additional training, even time in Virginia for a three-week ground crew TDY (Temporary Duty Assignment) that we called the “Can’t Do That Tour”. There was time in Nevada too where we stayed in a Las Vegas strip hotel. After all, we were RAF. We don’t dig in; we check in. The Royal Air Force was a great job but eventually I retired. It was an easy transition into a civilian team doing much the same job, bomb disposal. It was like a promotion from a military rank to simply being a “mister”.

I know plenty of chaps who still talk about their lives as if still in the military. They just didn’t adjust to having the military brainwashed out of them. Some are suffering from PTSD. The UK just doesn’t have the same understanding and respect for veterans like what happens in the USA. We are made to feel embarrassed when asking for a military discount. But for me, I just closed one chapter of my life in order to start the new one. Perhaps it was easy for me because the job was much the same.

I was then out to discover UXOs that lay in wait where wind farms were meant to generate power and where new housing developments were to be built. Like the military protocol in the RAF, there was also a protocol when working with my civilian team. After all, the military just can’t go out looking for explosives. Ninety percent of the time, nothing would ever be found. It’s the ten percent that matters. Civilian teams are needed to do this job of searching. Our service is invaluable to the clearing of areas where new construction sites are planned, especially in places where the foliage is reclaiming the rubble from bombed out Victorian buildings. It’s my job to carry out reconnaissance and determine the potential location of any UXO. Part of this involves visual interpretations, study of historical aerial maps, and the use a magnetometers to gauge changes in the subterranean soil. When a UXO is found by my civilian team and me, the military or the police are called in to dispose of it. But the most important part is still my job, the active role of finding and defusing the dangers before they explode.

Unexploded ordnances are a real problem in Germany. Experts estimate that 1.3 million tons were dropped by the Allies. As many as twenty percent of them were duds. Many are still buried in the ground. During the summer of 2019, just north of Frankfurt in the little town of Ahlbach, a decomposing, 550 pound bomb spontaneously exploded and left a thirty-three feet wide crater, fourteen feet deep, in the middle of a barley field. No one was hurt that time but who knows about the next time. And a next time is sure to come.

As a bomb decays it becomes more and more unstable. It becomes temperamental and more sensitive to being dug out. The job of disposal gets harder and harder. The job is still vital but there have been recent, drastic reductions in the military and the building industry often needs to be convinced that the threat is real. At one point, it was thought that the discovery of these UXBs (Unexploded Bombs) would decrease over time and the need for EOD (Explosive Ordnance Disposal) would also decrease. But, the need is still with us. Unexploded bombs are still being found. There’s still more of them.

During the 1960s 101 bombs were recovered in England. One-hundred-and-fifty-five were found in the 1970s including five on the center line of construction for the M25 motorway. There’s no way to determine how many are still there or exactly where they are hiding. The threat of an explosion still looms in the air as chemicals degrade and metal rusts underground.

The bomb I defused on August 22, 2015 was buried under the basement floor of a Bethnal Green, three-story building in East London. It was found by a construction crew and still had its tail fin intact. One-hundred-and-fifty people were evacuated, traffic was diverted, and it took block and tackle to lift it out safely. At the time, it was one of nine bombs found in London since 2009. More have been found since then. After all my training, finding and removing that one bomb was like a job reward. It was like finding the Holy Grail. My expertise made a difference.

III.

I am the air, the invisible gaseous substance of mostly oxygen and nitrogen that is needed to sustain life on earth. I am the elusive atmosphere, one without a definite shape or volume, one of four classical elements in ancient Greek theory, something considered a driving force in the birth of the cosmos, something existing between fire and water, something that engulfs history. I foretell the future through unwitting humans who feel my presence and even say, “There’s something in the air”. That’s me, the aura surrounding everyone, everything, always. Air.

My shift-changing nature runs the gamut from the elation after defusing a bomb to the paralyzing fear that one might blow up. I was there when the German Luftwaffe dropped more than 100 tons of bombs and assorted incendiaries on sixteen cities in the UK. In the eight months known as The Blitz, some 43,000 civilians were killed and at least 1.1 million houses and flats were damaged or destroyed. One of every six in London were made homeless at some point. As air, I carried the whistle of bombs dropping and of sirens screeching in the night. I echoed the cries of the dying. In me hung the intense fear of the unknown, the all-consuming fear of bombs.

As air, I permeated the lungs of every Londoner who sought shelter underground and my effects have been long lasting. In fact, my mixture of fear and curiosity are still afloat. In 2016 Thames and Hudson published Laurence Ward’s London County Council Bomb Damage Maps, 1939-1945. Toni Fiteni has a copy. In it, he keeps the newspaper clipping of his successful bomb defusing. He regularly thumbs through the 110 reproduction historical maps that document the city’s war time destruction. Color-coded markings map the impact of exploded devices. The tome does not, however, identify the potential ten percent dropped that didn’t explode. It can’t. Those bombs are still waiting, decaying.While the bombs wait, I drift in the subconsciousness of human minds. I am ready to spread fear on by-passers lips, in every new media’s lead story, and through public hysteria.

My aura of fear has already seeped into everyday English vocabulary. There are movies that bomb at the box office and performances that bomb all over the world’s stages. People talk of dropping the L bomb and the F bomb, each a stunning and often shockingly negative piece of unexpected news. There’s a ticking time bomb and a state of total inebriation. Being a blonde bombshell like Jean Harlow and Marilyn Monroe isn’t held in esteem anymore. It comes with dumb blonde jokes and plenty of sexual harassment on the corporate level. Only the amusement of a photobomb seems to have lessened the tension swirling around the very word “bomb”. Sometimes, bombs are the butt of a joke and everyone actually laughs.

As my grip of fear dissipates over time, I know that there will be vestiges of the past that want to be found and eventually will be found. These moments of discovery will restore my aura of anxiety. It’s like R. C. Russett’s dog tag. Toni Fiteni found it when clearing a landfill of Victorian rubble mixed with the remains of an American base. This was a highly suspicious area for UXOs. A Google search found some information. The soldier was stationed in the UK in 1943. He died in 1983. But to Toni, this dog tag is a relic from a scary past and a reminder to appreciate history. It is a reminder that other bombs are still waiting to explode. All over the world there are countless numbers of mines, UXBs, stockpiles of lethal chemicals, and weapons of war. The lists are largely forgotten as the past is being swallowed by the future. Yet every once in a while, a bomb is found and fear is unleashed. The EODs are called in to defuse the situation. As air, I infiltrate the scene that is trying to come to terms with the loss, with the bombs, and with the need for people like Toni Fiteni who dedicate their lives to the disposal of explosives in favor of a better world.