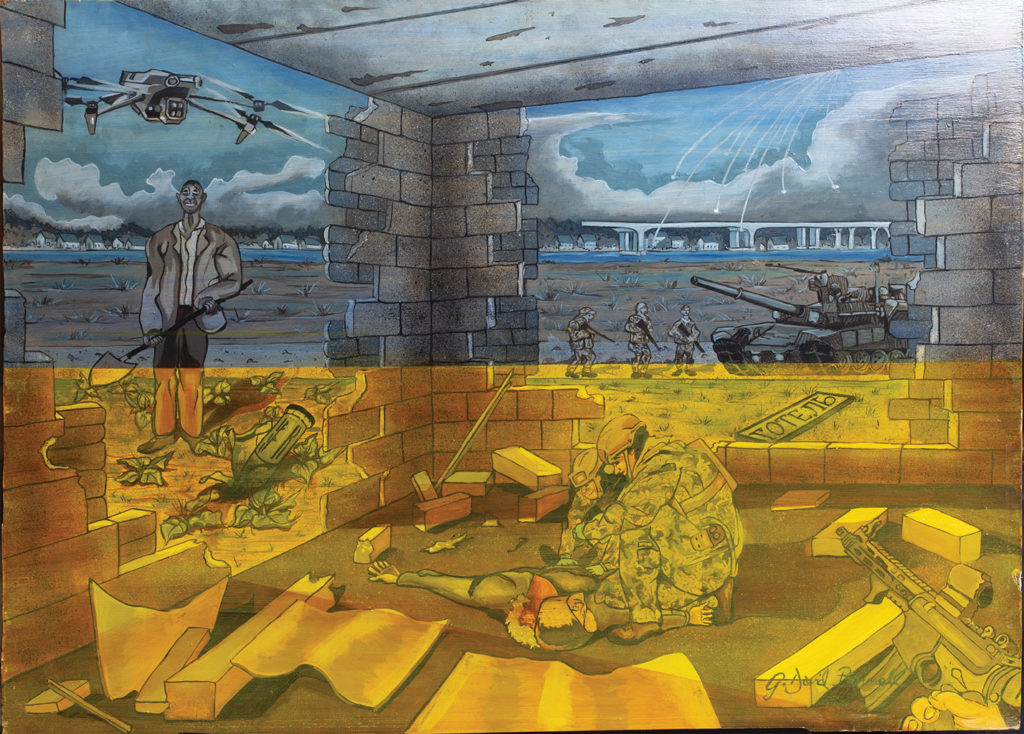

G. David Burnell

30″ x 22″ • Oil and Glass shards on board

Artist Statement

I really enjoyed interpreting Sergio Alarcon story of volunteering to fight for the Ukrainian people. It wasn’t all about one particular battle. It was all the pieces that created a whole. He spoke so softly and authoritative about death and trying to save civilians. Caught in the crossfire of war. The new drone technology. Phosphorus gas! Training soldiers in their 60’s that retired just months before this all started. Just an amazing human.

As an artist I wanted to connect to an audience and hold their interests connecting with Sergio’s memories and the sum of his amazing bravery.

by Compton Bailey

“Beyond this place of wrath and tears

Looms but the horror of the Shade

And yet, the menace of the years

Finds, and shall find me, unafraid.”

– Invictus, William Ernest Henley

Too often people mistake the harsh perspectives of veterans as being a product of them being broken. They see the potential of the world through the style of rose-colored glasses veterans fought for them to possess. Yet when they return, they’re ostracized for bringing some of the war back with them. Instead of considering the memories to be like mental dust needing to be knocked off, they are put in the box of “broken” and forgotten.

“I don’t feel broken,” says Sergio. He has been back from Ukraine for about two weeks at the time of our interview. Looking back on his six years in the Marine Corps, deployments to Iraq and Afghanistan he volunteered for, and now three months in Ukraine, and the things he carries with him from the wars,

“The only person I have to point the finger at is myself. I’m the one who enlisted in the Marine Corp.”

Sergio grew up in Massachusetts, the son of an international salesman father who freely admitted “I just make rich people richer,” something he wanted no part of, and a mother who, before her death, instilled in him that there was nothing better or more important in the world than serving others. He felt a need to give back to the country that had given his immigrant family a better life. They never knew what to make of his decision. None of his friends or their families had served either. He had no way of knowing what it would entail, but he knew they would put his body through hell and very possibly require him to give his life. He signed on the dotted line on the west side of the Mississippi River, a Hollywood Marine.

He is blunt in describing the process of training men to kill.

“People have to be brainwashed”

He doesn’t hesitate to use the word,

“To hate and dehumanize an entire group of people. The same methods of indoctrination that are used by militaries of murderous dictatorships and democracies alike. I hate to break it to the world and especially America,” he says, “but we do the same thing. How many times did they say Kill Kill, kill them in boot camp or start a lesson with a video of Marines killing the enemy, or being fired on by snipers? When the lesson ends, your nerves and your whole body, your mind just wants to say kill, kill them all. We even have songs when we run about strapping bombs to the fucking kids…How morbid is all that?”

It took conscious effort to remember he was indoctrinated.

It was an abrupt change, going from a Mormon missionary knocking on doors in Portland to boot camp, then advanced training, gun in hand, ready to give all for God and Country. But in other ways, the career change was a logical progression. His MOS was 7051, Crash and Fire Rescue, a small specialty. He had experience in the field, having volunteered as a firefighter since he was 15, a job he does professionally now at the federal level. “

Fire is fascinating, a living breathing thing. You can kind of predict what they’re gonna do. But then right when you think you’ve got it, it fucking bites you in the ass.”

He thrives in the uncertainty. To be good at the job, you need to be able to stay detached, slow down, and get as complete a view of the situation as possible. Get overly emotional, and you make bad calls. No one wants the guy coming to their rescue to be hyperventilating. When he is in a fire, time slows down. It’s Sergio’s normal, surprising as it was for his therapist to hear.

He volunteered to deploy to Iraq when a team was a man short, when he was still arriving there three weeks shy of his first year in the Marine Corp. They were tasked with rescuing trapped servicemen from convoy vehicles that had been hit by an IED, a frequent event in Iraq. They’s arrive by whatever aircraft was available, usually going in under yellow conditions and when there was enemy contact within a couple clicks. Besides the obvious dangers, there was a constant sense that none of the population could be trusted, not even the villagers with whom they broke bread. Sergio didn’t hate them, he felt genuinely sorry for ordinary Iraqis, but in a country with an unfamiliar language and culture, where attacks by domestic and foreign militants who wore no uniform were a constant threat, distrust was only logical. The interpreter his unit worked with informed on his entire family. They were hiding weapons to be used in attacks against Americans. But the fact that he sold them out for a chance at a better life, made him particularly untrustworthy, especially for a man they needed to be able to trust with their lives.

He won’t talk about the details of his deployment to Afghanistan, he was asked not to for security reasons, but he does offer that he volunteered when asked, even though it meant extending his enlistment by two years and leaving his pregnant wife alone for several months.

“Getting out and returning to civilian life was a mind fuck”.

He found adventure, belonging, and a sense of family stronger than what he had known growing up. His family wasn’t there to greet him when he got home from deployment, it had just been him getting off the bus and going back to the barracks.

He was working as a federal firefighter in Charleston, SC when Russia invaded Ukraine-or rather expanded its 2014 invasion, seeking to go beyond the illegally annexed Crimean peninsula. Sergio accepted, like nearly everyone in the west who looked at the numbers, and what we thought we knew about the Russian military, that Ukraine was fucked. Then Russia failed to take Kyiv, and were turned back by the Ukrainians.

Sitting in his easy chair in the firehouse, waiting for the alarm to go off, while the most intense fighting Europe had seen in generations raged, felt wrong to Sergio. And this war had a moral clarity, clear cut black and white, that he had not found in Iraq or Afghanistan. Americans wanted to avenge the 9/11 attacks, but when they saw huge amounts of money sitting in the desert, and private contractors with better gear than his unit, he and others asked themselves why they were there. But here, Russia was the aggressor bent on subjugating the Ukrainians, who were fighting for their very survival against the people who had oppressed and murdered them for centuries. He had combat experience and training as a medic. When he told a fellow Marine he was thinking of going, he knew he was committed, he was going.

Three weeks later, after he had put his affairs in order, Sergio walked across the Polish-Ukrainians border with a pack and two rolling duffel bags that would have cost more than his one way ticket if the airline hadn’t waived the baggage fee. When he got out of the Marine Corps, he told his then wife that he was not out of the fight. Now he was in a country that wasn’t his, driven by a sense of responsibility to do his part in a righteous cause and hopefully make a safer world for his children; it was bad enough they had to worry about school shootings, a danger one Ukrainian pointed out even their kids didn’t face. He didn’t know anyone and his knowledge of the language was limited to Google translate.

He stopped at a refugee camp on the Ukrainian side of the border and was questioned until they were sure he wasn’t a Russian spy. Fifteen minutes later, a pickup truck pulled up beside him, and an American he calls Nomad, and a former Dutch soldier named Tim offered him a ride. According to him there are three kinds of westerners one meets in Ukraine. The first are those who are there to help, to do the right thing, without any desire for personal gain. The second are those who are lost and looking back to when they were at war, where they remember a sense of belonging and purpose, trying to find it again. The third, the ones you can find in every war, are in it for the money. Sergio and the others in the truck were the first kind. They got around and into the fight by networking with other volunteers. It’s a complicated process, key to it is talking to anyone you hear speaking English in a train depot, a store; places like that. Nomad in particular excelled at it. Something to remember for the sake of context: the country is full of hopes and dreams- people can promise you the world, just don’t believe it until it happens.

The first stop was Lviv, where on the second day, they were tried by fire when two cruise missiles flew overhead, so low he could almost read the numbers on the side. They hit a train depot and a hotel Sergio doesn’t know how many dead and wounded there were, but his team treated more than thirteen. It was their first time working together, their training took over and they managed it seamlessly. He didn’t sleep that night; it took a week before he got over it. They spent their days training Ukrainian Guard soldiers-about 600 total- in the nearby woods in tactics, maneuvers, medical procedures, small arms, whatever the commander wanted them to teach. Few of the men spoke English, so they used a knife hand and being grabbing, moving them to the proper positions, and diagrams drawn in the dirt to impart the harsh, bitter lessons in spite of the language barrier:

“Bunch up in that formation, and an explosion will kill you and the man next to you. Do that if you want, but you’ll be fucking dead.”

Some of them were fifty and even sixty years old, willing, but their bodies unable to keep up with the younger men. At the end of the day, exhausted they would shake Sergio’s hands and thank him for kicking their asses. He’d gone there for moments like that, inspired by the fact that the motherfuckers had heart and guts.

They left Lviv at the end of his first month. They spent five days near Kharkiv with other western volunteers, some Americans and a few Brits among others, running night reconnaissance, locating tanks for the others to take out. One night, a drone spotted them. Russia blanketed them with tank fire. Sergio’s right ear drum was blown out, and the South African on his four-man team was killed no more than 30 yards from where he stood.

Two weeks later, after a stop in Kyiv, he and Nomad made it to the outskirts of Donetsk and lived in a trench for a week and a half with Canadian volunteers, fighting together alongside the Ukrainian army to defend a nearby village. They stayed outside of the village itself, keeping the fighting away from its people. There are a great many Canadians in country, which is not surprising since Canada has 1.4 million citizens of Ukrainian extraction out of a population of almost 39 million, among them notable politicians (including the deputy prime minister) almost four percent of the population, many with active links to their ancestral home.

It was a different war than Afghanistan or Iraq. They were bombarded with Russian artillery, the main killer, starting like clockwork at 4 AM each day. Tired of waiting in a trench and being shelled rather than fighting, they moved on. They would be back, near Donetsk again later in his tour, running casualty evacuation (CAS evac) missions from a base next to a bridge. The phone would ring and report a location, and a number of two hundred and three hundred dead and wounded, respectively. They would drive out in a tank, or in the Ford F150 he and Nomad armored with scrap metal SAPI plates, to get the wounded. They had five to eight minutes to stabilize them before handing them over to medevac at a rendezvous point. They were often men he recognized immediately, leaving him the task of triaging men he had trained or thrown back a shot with along with dead and dying strangers in the bed of their vehicle.

More happened than there is room to recount. He learned to be vigilant of drones, an ever present hazard. You would have to be lucky to shoot them down, more likely, you’d just waste more in ammo than the machine costs. He went on a mission in a captured Russian tank, one the Ukrainians had repurposed, shooting and relocating after each shot. You can hear the exhilaration in his voice as he recounts it, and mentions the Go Pro footage he has, The F150 he was so fond and proud of-thankfully empty- was destroyed by Russian fire. And he saw phosphate (white phosphorous bombs) light up the sky, a sight he likens to a verse from the Gospel of Mark “the stars will fall from the sky, and the powers in the heavens will be shaken”. When it was time for him to leave, he made his way to the village where a Ukrainian friend back in the states had grown up, where there was food and good company. From there, it was on to Kyiv, then a 13-hour train over the Polish border, another to Warsaw, and a flight back to the states. There was a friend to greet him at the airport this time, unlike his other returns from war.

Sergio was out doing yoga on his houseboat just after he returned, not long before this interview, when a civilian drone flew over his head. He froze for a couple seconds before realizing he was home and safe.

Yet he misses it and wishes hadn’t come back. He would like to be there with the unit he ran medevac missions with, the men he knew when he lived under the bridge, and the commander who placed his faith in him, and the others who trusted him with their lives. Still, it would be a difficult choice whether to go or not if the option were there again. He hopes he will be remembered as one of the few good men, who fought there for a good cause, and lived up to the Marine Corps slogan. As of this writing, the village near Donetsk is still in Ukrainian hands. It took him less time to get over (again, a relative term) the loss of his South African teammate near Kharkiv than the cruise missile strike in Lviv. They were able to bring his body back and get him home to his own country. The souls of those who give their lives for others are in a better place than the rest of this world, he believes.

This was a hard view to take, made of harsh understandings built from even harsher trials. The war he chose to fight, filled with a noble cause, may lay upon him like dust needing to be knocked off. But with the right eyes… with the correct eyes of those engaged in battle… he is far more put together than broken.