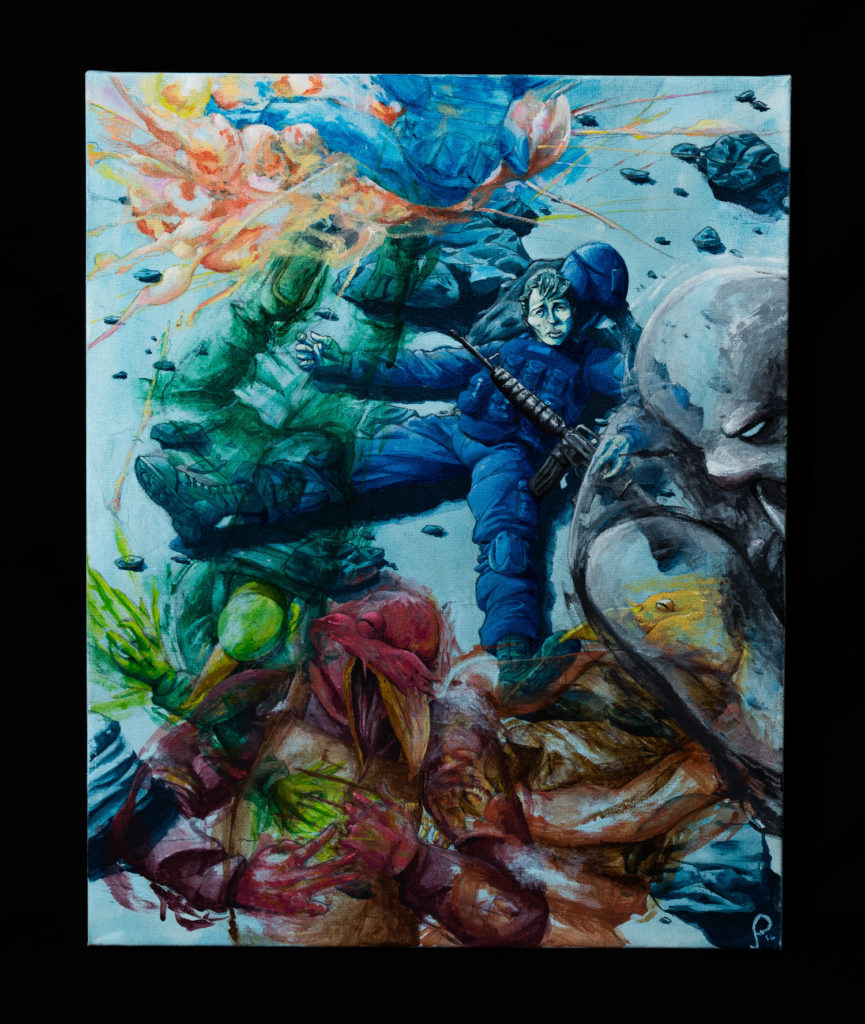

Sammy Lopez

Acrylic on Canvas

12″ X 24″

by Robert Leheup

“Be broken, O peoples, and be shattered; And give ear, all remote places of the earth. Gird yourselves, yet be shattered; Gird yourselves, yet be shattered.”

Isaiah 8:9

The heat didn’t give a shit. Not about the weight I was already carrying or my pregnant wife waiting for me back in California. Nor did it care about the bustling of nearby Marines, teeming back and forth from the vehicles and tents and a shared bloodlust set up as Camp Leatherneck. Instead, it slapped me across the face like a jilted lover or a spurned pimp, completely disregarding the burdens I was carrying on a thousand different levels. I was in the Helmand Province of Afghanistan. And it felt like home. I hoped this was wrong, of course. I wanted my time in this country would only be a piece of what my life would afford in time. So every few hours I’d look at the laminated photos I’d taped together and fall into their context. On one side my beautiful wife, Kelly, who is a warrior in her own right. And on the other, my unborn son, Dominik, caught in time and in utero, with a slight smirk, as though we were sharing a joke. Sometimes I’d even smile back.

War is fought through smaller battles. This one was lost to the den of raunchy jokes, heartfelt lamentations, heavy metal music, and people passionately declaring how much they “didn’t give a fuck.” And all mixed with the cacophony of clicking and popping noises inherent when cleaning our rifles and machine guns. I sipped from the cup of my world left behind, then joined my men playing card games while tobacco and energy drinks took the place of our meals. Most of us hadn’t seen combat at the time, so we would sit together, fantasizing about random scenarios where we would kill our enemies with vengeful prejudice. We were hammers, beaten into form by our seniors, our training, and our imagination. So we made everything into nails. The harder, the better.

But this wasn’t enough. Though we each had our own motivations that lead us to this point, none of them were fantasy. We didn’t just want to be there; we had to be there. So when the time came for the breakdown of our next mission, we weren’t simply eager, we were foaming at mouths made entirely of canines, our eyes open, our will ready. From there, we received our gamut of ammunition, rifle rounds, smoke and fragmentation grenades with their pull-pins and thumb clips, mortar rounds to boot, and topped off with grenades made especially for the launcher underneath my M16. Our packs got heavier, but morale improved. We set up our packs in a row roughly a hundred feet from our helicopters, the night sky looming over us with dark, familiar purpose. I found a friend of mine, David Baker, who had approached the British troops at one point. We began making friends and I traded a parachuted

flare for a 40mm phosphorous round for my grenade launcher. David would be killed several months later, the victim of a landmine placed in the middle of a corn field. From there, I walked over to my friend and squad leader, a rare combination in what would elsewise be considered the strictest of environments in American military protocol.

From there, with as little melodrama as possible, a feat extraordinary given my nature at the time, I made reference to the folded flag I had at the top of my pack, and how I wanted him to give it to my son if things didn’t work as planned. He nodded to me nonchalantly. “No problem, brother. I promise.” With that, he raised a pack of Marlboro’s to his lips and we left it at that.

Loading onto the helicopter was a terrifying experience. The whir of the engines firing up, green monocular night vision goggles piercing the night like beasts, and the smell of fuel mixed with body odor, foot powder, and Copenhagen long cut, were telltale signs of men coming to terms with

their reality. This was made all the more visceral when I put on my own NVGs, the green hue casting an uncomfortable, eery light onto all of us. I turned to a fellow team leader, Josh Ibanez, who racked the charging handle of his rifle, loading it, along with a grenade in his launcher, then slapped the buttstock as though he were in mid coitus. I laughed in spite of my fear and gave a thumbs up to my teammates, who responded in kind.

No bullets flew passed us, no sound of metal tearing metal or the high pitch of a missed bullet. The helicopter landed and we began filing out, but the weight of my pack took hold and I pitched forward, panic rising in me as I watched boots file past, the men wearing them too focused on their own goals to help. And then Claudio Patino, one of our snipers, lifted me to my feet and asked “Are you okay, bro?”

This man was a warrior in the truest sense, the idea of unit cohesion rising beyond his own ego or need for self-preservation.

This was proven again immediately as I stepped out of the back of the helicopter and into five feet of black water, unable to move from the weight, drowning, when Patino pulled me back up a second time, soaked to the bone and disoriented. He would die in a bold and selfless act during a firefight several miles north and several months further from where we were.

As I collected myself, shadows ran across the treeline like shadows by a fire. I raised my weapon, my heart pounding, but they were gone as quickly as I’d seen them. Trudging onward through the flooded field, I reunited with my Marines, the rotor wash from the helicopter fading as the ripples in the water calmed. We formed a circular perimeter, each of us quietly cursing the black mud reaching to clog our guns. The plan came down that we were to wait until daylight to begin our assault. Until then, we

would take turns sleeping, half on guard, half catching what fleeting shuteye we could. I remember thinking “No one in their right mind could go to sleep right now.” And then someone to my right began snoring.

As the sun made its grand entrance, we rose like the walking dead, the chill of morning quickly turning to heavy, damp heat. In order to avoid any booby traps, we moved from one flooded field to the next, shifting our bodies to convey the weight we carried. At one point, we reached a long ditch, filled with stagnant water and lined with trees. As my point man and automatic rifleman came into the open field, three small explosions occurred immediately in front of their boots, coupled with three auditory snaps. I yelled for them to “Get down!” From there, my team sought solace in the trees, my voice echoing over the radio as I requested from Denning that we return fire. Another voice called over the radio.

“Did you just ask if you could shoot back?”

I felt my cheeks flush and tugged at my body armor. I spotted movement in the treeline across the open field, just behind the ledge of a low driedmud wall. I raised my rifle when one of my comrades shouted “He’s got a gun!” And he launched a 40mm grenade toward the assailant.

The time for subtlety was over. Half a second later and I’d loosed a grenade of my own, with two other squad leaders soon following, the explosions landing like dominoes fall.

Two seconds later and debris fell like snowflakes and feathers… and rocks.

Fast forward a cleared compound and a couple of hours later and we’re sipping chai tea with a man whose backyard had been our combat zone, gutlaughter and schoolyard giggling bubbling up at the incredible, untenable circumstance in which we’d found ourselves. Being the vigilant man that I am, I used the time to investigate where I was. A little situational awareness never hurt anyone. Searching the mud palace, one room had ornate rugs meticulously rolled and stacked, floor to ceiling, as precarious as my circumstance. The next held white sacks filled with grain, with a couple of women dressed head-to-toe in burqas huddled with five small children in the room farthest from us. The whirlwind of patient fear in their eyes struck me still for a fleeting moment, then, with warrior’s resolve, I returned to our generous host.

He’d served the tea from a polished metal kettle,wooden handle tilted with care through calloused fingers. His gaze skimmed the room, his forehead tightening when he’d counted us. Without skipping a beat, he darted out for more glasses, sweat evaporating from his forehead before it could bead. But it wasn’t us that had him concerned. He needed to follow the custom of Pashtunwali, providing us shelter and sustenance as we were pursuing (or could be pursued by) a common enemy. I had shed the burden of my humanity, and embraced the beast within myself. The civility offered by this man had me dumbfounded. At the time, I didn’t know that this would be the same code that would later allow the local Pashtun tribe to exact revenge on us for the unfortunate death of a young boy named Mahmoud, killed during a nighttime firefight.

Not knowing this at the time, we thanked him and continued our journey, the firefights ahead a far more comfortable idea than the subconsciously invasive nature of his hospitality. I was more comfortable walking the fields, the random whip-crack of rounds hitting the ground at the feet of our patrol a reminder of our singular purpose. We were warriors, fighting through heavy heat to find sweet reprieve from the weight of the sun with the intermittent shade of sporadic treelines. The Taliban were running scared, and rightfully so. We were out of water, food, and patience, our struggle only making us more deadly, our violent nature leaving a smile on our faces with the acknowledgment of our duty. After a time, the burden of a lack of supplies showed itself in my own corporeal dissociation. I’d look down at my legs and wonder how they were walking; look at my arms that seemed so distant. Then I’d look to my brothers and drove on.

When night came, we would lie in prone, making a compass of gun barrels to keep a steady security of our perimeter, claymore mines several yards in front of us to cover enemy avenues of approach. We’d take turns sleeping, the soft, cool grass making for a perfect bedding for our exhausted troop, while those on post were left with the darkness and their imaginations. The end of my watch never seemed to come fast enough.

And then the day would begin and we’d start walking. This lasted for well over a week. We’d walk, get into firefights, find explosives, search compounds, rest, then walk some more. Thirty two miles in five days, at one point. With full combat gear and supplies thinner than the line that draws the horizon.

At the time, I wasn’t religious. I had “Catholic” stamped on my dog tags, ensuring the style of my funeral, but beyond that, hadn’t given it much thought. But one day, while an exhausted catharsis pulsed through my bones, I puffed on the cognac-soaked cigarillo given to me by Cardi, laying on my back with my rifle within arms reach, and I thought of Jesus. I thought of the weight of the cross he was scourged to carry through muddied streets to Calvary. And I felt his pain.