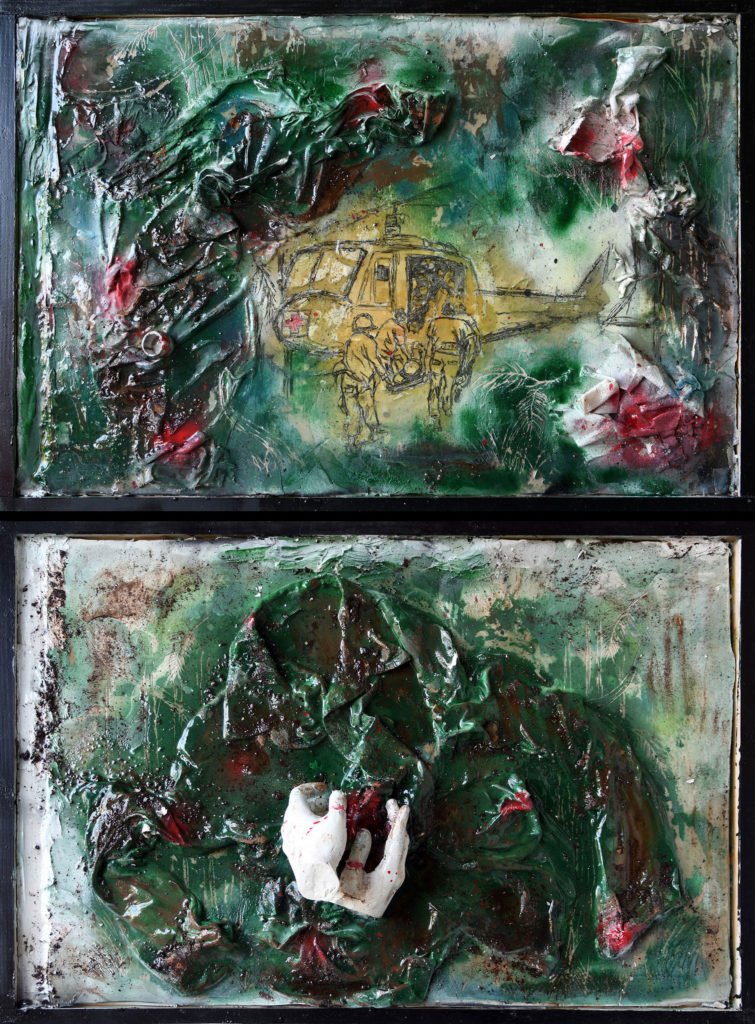

Kate Frost

36” x 24” • Painting and Drawing on Engraved Plaster

The baggage and weight that veterans carry back home can restrain them from being free from their past. For years they can try to push back the many visions of pain, suffering, and violence they witnessed and endured. This work acts as a visual advocate for the voice of this veteran. It magnifies it through plaster and other techniques, in hope to raise awareness about what veterans face when returning home.

Inspired by the experiences of Jonathan Sitman

More than a Drop

by Jonathan Sitman

I spent all my time up on the DMZ.

I flew in a Medevac Huey where most walked

and humped thru jungle and trees.

Flying out of Quang Tri responding to a call,

We saddled up and headed out in late fall.

The coordinates brought us to a jungle floor.

An ambush had taken place the night before.

We picked up wounded and brought them through the doors.

Some of the soldier’s receiving life-threatening needs

that demanded our immediate attention in stopping them bleed.

I went through the motions of helping these men

just as I’ve done for others before them.

Holding plasma, giving comfort, saying, “we would be there soon,”

or “try and hold on,” was the common message from us few.

We finally get them to the triage where we flew down to get them in. Later,

as I clean off the deck seeing from the days flight,

I begin to recall the echo of the days fight.

It became another day I wore on my hands and clothes

the blood of my brothers whose names were unknown.

Their blood stains covered me like splattered paint,

spilling so indiscriminately all over the place.

I felt the burden and weight of their life changing fate

that weighed heavy and deep and becoming so great.

I would have preferred the color of clay or mud

or the stench of fatigues worn and torn from the jungle and sun.

Instead, I wore their blood with anguish and fresh pain,

recognizing their need from receiving deep wounds that day.

There was no distinction between any blood type;

it could have been “A” or “B,”

or from O positive to O negative type.

It didn’t matter, it was all red,

flowing from each one of them. It was a premium liquid, like a rare gem,

this red fluid that was coming from within them.

I wore this color and its odor like it was part of my uniform, like a unit patch, insignia, or rank that was worn,

because it was part of the routine of everyday war.

When it was exposed, it began taking on different forms,

turning things rotten with a stench down to the core.

When it flowed, it changed whatever it touched,

from clothing, to bandages, to the body it left.

I spent time trying to wash it off.

Scrubbing and scrubbing and not able to tell

if I had gotten it all off or not,

turning my skin raw and red

because it clung to me like part of my skin.

It became morbid when worn all day and drying hard as a shell. It kept you aware of its presence and soldier’s as it continued to smell. It came with the uncertainty of recovery to its blame. Its flow carried with it sorrow and unimaginable pain. It only stopped when the right pressure, tourniquet,

or dressing was maintained,

or when it ran out and completely drained.

The deeper the wound, the louder the screams,

only to stop from the shock it would bring.

This was not from strange or distant men;

this was from our own soldier’s trying to defend.

The burden was heavy, even without knowing names from an element of mental and physical strain.

Its infection can continue to press

as I wake in a cold and unfiltered sweat,

when one of them comes to me in a nightmare

exposing again the whole days event.

It is the common color and fluid of war.

I cry out, “Please, no more!”